With the murder trial of art fraudster Brian Walshe in full swing this week, I thought I’d share a piece I wrote for the Boston Globe about the Warhol scam that first landed him in hot water.

Brian Walshe, who now stands suspected of murdering his wife, Ana, as the holidays drew to a close, first came to the notice of law enforcement two years ago, when he was arrested for an elaborate scheme to monetize a South Korean friend’s paintings, which included valuable works by Andy Warhol. Walshe sold his friend’s paintings on eBay to an art dealer in California, but he shipped counterfeit Warhols instead. As is often the case, the fakes weren’t very good, and the Californian quickly realized that they weren’t what Walshe purported them to be.

As we’ve since learned, and as has been reported in this newspaper, Walshe’s list of deceptions runs long, including apparent swindles of his father and at least one friend that garnered him $1 million. And now his prolific and amoral quest for a lavish lifestyle has been brought to the fore. It’s a characteristic of many art cons.

In the early 2000s, a struggling artist named Wolfgang Beltracchi had a bold plan: He would use his unappreciated skills with a paintbrush to imagine what some of history’s most famous Impressionists might have created — but didn’t. He took to fabricating works by Heinrich Campendonk, Fernand Léger, Max Ernst, and others, but not merely for his own enjoyment. Beltracchi and his wife, Helene, concocted a backstory for the forged collection in order to sell them for top dollar. It would be the Flechtheim Collection, cunningly named for Alfred Flechtheim, a collector and journalist who was persecuted by the Nazis. The couple falsely claimed that Helene’s late grandfather had rescued the so-called degenerate art that the late Flechtheim had saved from the Nazis during the Second World War.

Beltracchi’s creative skills didn’t end when the paint dried. Knowing that provenance would be key to selling the works, he made counterfeit gallery stickers and affixed them to the backs of the canvases; he added false stamps to them; and, the coup de grâce, he posed Helene as her own grandmother near the art and photographed her using a period camera, paper, and developing solvents to fabricate images that “established” the paintings’ authenticity. The scheme grossed the Beltracchis $45 million.

I interviewed two of the experts who applied scientific testing to prove Beltracchi’s works were fakes. Contrary to lore, Beltracchi’s forgeries were not particularly masterful. Indeed, they were rather easily proven to be forgeries. While the most famous mistake Beltracchi made was using titanium white — a color not available at the time the actual artists worked — there were plenty of other telltale signs of fraud. The scientists told me his works had an “obviously fake patina,” issues with the stretchers, inconsistencies with the labels, and “a range of physical anomalies.” However sloppy, the work fooled many so-called experts.

I’ve investigated, researched, and lectured on art crime for the better part of two decades, and I’ve learned that the nerve of the conman is more essential than the talent of the forger. Based on sheer misguided gumption, they take their phony wares to market and often trick dupes who so badly want to believe that they have come upon a great deal that they suspend disbelief and make the too-good-to-be-true purchase.

Such bravado is the key ingredient to the art scammer. It takes a remarkable amount of nerve to take a worthless painting and bring it forward to connoisseurs and demand upwards of hundreds of thousands of dollars in return. And this heightened sense of self and the concomitant level of esteem afforded one’s own intellect often lead the criminal to make shockingly sloppy mistakes that lead to their downfall.

Walshe’s art fraud was not dissimilar from those of many other criminals. The Warhol was an unconvincing fake; the art was in the con, notably in the audacity of the conman. Walshe’s victim in the Warhol scam told the media, “I’ve bought over a thousand Warhols, and this is the one and only acquisition that got by me. He was that good. Clever playbook and Oscar-worthy performance.”

Born wealthy, Walshe did not need to turn to faking Warhols to finance his lifestyle. But art forgery is not a crime of necessity. It’s rare to find an art fraud scheme that is born of desperation. Whereas paintings have been stolen by people suffering from drug addiction and sold for fast money, no fake paintings have been created, complete with a fabricated provenance and sales pitch, in order to feed an addiction or pay off an angry bookie. They are the product of schemes that are often fueled by a sense of entitlement and visions of grandeur. Larry Salander, a major Manhattan art dealer known for his opulent gallery and remarkably lavish lifestyle, landed himself in prison with a harebrained scheme in which he sold to the rich and famous partial ownership of valuable paintings that did not belong to him, resulting in title percentages that far exceeded 100 percent in total.

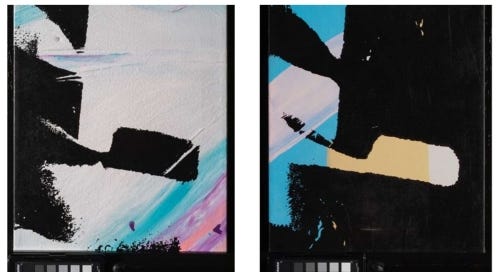

Bogus paintings also serve the antisocial criminal by feeding his need for affirmation. Murderer and kidnapper Christian Karl Gerhartsreiter, known to Bostonians as Clark Rockefeller, possessed fake Abstract Expressionist paintings. In his book “Blood Will Out,” Walter Kirn recalls seeing a painting in “Rockefeller’s” apartment purported to be by Mark Rothko; it had a dog hair stuck to it and smelled of fresh oil paint. Gerhartsreiter went so far as to have someone posing as an art restorer come to clean the work while Kirn was visiting. (Art restorers don’t typically work on masterworks as they hang on a wall.) Such an ostentatious display was key not only to Gerhartsreiter’s pose as a fabulously wealthy Brahmin, it also helped fuel his ego to be so careless with a canvas that, if authentic, would have been worth tens of millions of dollars.

There are similarities between Gerhartsreiter and Walshe that cannot be missed: Both seem to possess Superman complexes that require the symbols of great wealth to validate them. And each man seems to have the ego to believe that he has the intelligence to pull off large scams over those of lesser intelligence — namely, the rest of us.

It’s a common theme in art forgeries, and, unfortunately, it appears likely that it can be connected to far more horrifying crimes.